Note: This is an edited re-post of something I wrote in 2019 on a now-defunct blog, apparently a month before I started my first job in tech. I need to reference it in a future post. As a result, it is a little bit different stylistically from my current writing. I hope you enjoy it anyway!

I'm talking about the brain-destroying threat that narratives pose to our thinking today, and we must credit Nicholas Nassim Taleb's Black Swan for introducing me to the concept. It is the single most influential book on my life. I love most things that Taleb writes, but this is a controversial opinion, to say the least.

If you don’t know anything about Taleb, oh boy are you in for a treat. Here is a quote about the man to whet the appetite:

I know many of you love this guy, and think he’s a genius. I can assure you, none among you, are as impressed with his intelligence as he is. This guy is just insufferable. I’ve actually never witnessed a marriage of incompetence and confidence so fully and grotesquely consummated in the mind of a person with a public platform. This is the most arrogant person I have ever had the misfortune of meeting. When you meet him you quickly discover that he radiates a sense of grievance from his pores in a way that few people do. It’s kind of like a preternatural force of negative charisma. He is a child in a man’s body. And the mismatch between his estimation of himself and the quality of his utterances is so complete and so mortifying to witness in person that you just find you’re jumping out of your skin.

— Sam Harris1

I. Narratives Make Bullshit Sound Unreasonably Compelling

Here’s the message from Taleb that I want to discuss: You don’t know that much. You can’t possibly know that much because you’re just a human, and the least you can do is be clueless with your eyes open. A huge number of things are just too complicated to understand, but we are great at convincing ourselves we know what is happening. And one of the main ways we do this is telling stories.

A large amount of the book could be summarized2 as:

“Structuring your theory into a story makes it more compelling.”

Everyone knows that. You knew that, right? This is the most common piece of trite writing advice doled out to struggling university students, and I still give it out. Write a story. Facts? Haven’t you turned a damn television on in your life? Does it really look like facts are what’s going hot right now? It’s usually narratives that are selling.

Is that harmless? It’s just a way of communicating, after all. Of course narratives make details go down a little bit easier. There is a wonderful sense of coherence and closure. The project failed because the market was too immature. The surgery was botched because the surgeon didn’t sleep enough. J.K Rowling succeeded where all those other authors failed because she was so persistent. Start, middle, end. Get the hell out of here Taleb, no one needs you.

And wipe that smug grin off your face.

Those were my exact thoughts the first time I read the The Black Swan. I gave it an increasingly irritated read, chucked it ignominiously on a shelf, and told everyone it was garbage printed on trash.

Then I spent some time at university and started to notice a few unsettling things. It started in my third year when, on a whim, I picked up The Black Swan again on a flight to my home country for the holidays. Something clicked this time, and instead of sleeping the flight away, I was glued to the book. I stepped off the plane thoroughly sleep-deprived, but with liquid lightning running through my brain.

You see, I had just seen a TED talk by psychologist Paul Piff with 3.5 million views, titled “Does money make you mean?”. Here’s a summary (in his words) of the study – this will be on the exam:

“I want you to, for a moment, think about playing a game of Monopoly. Except in this game, that combination of skill, talent and luck that helped earn you success in games, as in life, has been rendered irrelevant, because this game’s been rigged, and you’ve got the upper hand. You’ve got more money, more opportunities to move around the board, and more access to resources. And as you think about that experience, I want you to ask yourself: How might that experience of being a privileged player in a rigged game change the way you think about yourself and regard that other player?

So, we ran a study on the UC Berkeley campus to look at exactly that question. We brought in more than 100 pairs of strangers into the lab, and with the flip of a coin, randomly assigned one of the two to be a rich player in a rigged game. They got two times as much money; when they passed Go, they collected twice the salary; and they got to roll both dice instead of one, so they got to move around the board a lot more.

[trendy man talks some more]

And here’s what I think was really, really interesting: it’s that, at the end of the 15 minutes, we asked the players to talk about their experience during the game. And when the rich players talked about why they had inevitably won in this rigged game of Monopoly … They talked about what they’d done to buy those different properties and earn their success in the game.”

– Local Bad Scientist

Wow, stop the presses! We’ve figured out why rich people are awful!

How much do seats at a TED talk cost anyway? Five thousand dollars? Paul, please, this isn’t the right venue to flex … wait, are they applauding you? There is something deeply pathological going on here, and it is above my pay grade.

It turns out all your personal biases were totally right! Everyone doing better than you is a jerk. It’s so simple! Wealth makes you into a monster.

“What we’ve been finding across dozens of studies and thousands of participants across this country is that as a person’s levels of wealth increase, their feelings of compassion and empathy go down, and their feelings of entitlement, of deservingness, and their ideology of self-interest increase. In surveys, we’ve found that it’s actually wealthier individuals who are more likely to moralize greed being good, and that the pursuit of self-interest is favorable and moral.”

“And that is why I am pumping chlorine directly onto the most expensive seats!”

– Paul Piff, probably.

There are plenty of technical reasons to doubt this result, ranging from statistical objections, to simply knowing that a lot of trendy scientific findings are false. But there’s a much simpler red flag.

Think about this for a moment, really stop and imagine this – how stupid would you have to be to get double the money in a Monopoly game and get to roll twice as many dice as your opponent, and still think you won because you kick ass at Monopoly?

Really, stop and think.

If the answer is unbelievably stupid, congratulations! It turns out it actually is unbelievable. If you didn’t get this answer, please see me after class.

Gregory Francis, a professor in the U.S, has spent a great deal of time drawing attention to dubious studies, mostly by working over their statistics. He is, to use the modern vernacular, a total dork. However, we forgive and like him here, as he demonstrates with some basic statistical concepts that Piff’s studies are turning up positive findings much more frequently than they should, even if we assume the effects are real. He just did the math and said “For a real effect of the size you are reporting, your method for detecting it would fail about half the time. Why are all your results positive?”

As an aside, Francis has previously accused authors of running tons of tests and failing to report the non-significant findings. One accused Francis of checking tons of authors and failing to report the innocent ones. The skepticism ouroboros has formed and the epistemology serpent has eaten its own tail.

Anyway, in Piff, we have an author in a field that famously has trouble replicating studies, proposing an implausible effect, with strong evidence that something is wrong with the studies coming out of his lab. I have no idea what he did wrong, and it’s entirely possible he has no idea either.

I told some of my friends (who are incidentally some of the top psychology graduates in the country now) that something suggests there’s an issue with the study, and asked them what they thought it was.

Ah, the problem is clearly that the sample size is too small!

Ah, the problem is that Monopoly does not generalize to the real world!

Ah, the problem is the sample was too homogeneous! (They just assumed that the university, like all others, were running everything on coerced undergraduates.)

Whether or not these critiques are valid, no one said “Come on, that’s just silly. People aren’t that obnoxious. I’ve met some morons, but there’s an upper limit.”

You see, I have no idea whether money makes people immoral. Hell, it probably does! I’m left-leaning, and I will certainly consider eating the rich if only ironically. But that’s irrelevant right now, and best handled in therapy.

No, the real point is that the claims from this study are ridiculous and intelligent people that have been studying for years can’t pick up on it. The real point is that I am actually really confused as to how Piff got his results, but at least I’m not tricking myself into thinking I know what’s going on. Did he fudge the numbers? Was the experiment poorly set up? Just pure bad luck in sampling? Hell, is the result true? I don’t know, but I will say that you don’t know either.

The problem with narratives is that they make everything sound convincing even if they really shouldn’t. The problem with this result is blindingly obvious – a twelve year old would object to your victory under this ruleset, and the objection would be sustained. But we stick a little story on here – “The ridiculous result makes sense because…” and suddenly it gets past intelligent people.

Narratives are indiscriminate. Attach them to anything and they are now more compelling.

A useful way of thinking about persuasive techniques is how Scott Alexander frames them as either asymmetric or symmetric. An asymmetric weapon is only helpful if your point is correct – you will get frustrated quickly if you try to use the scientific method to prove that the earth is flat. However, speaking in a clear voice and being very handsome are symmetric. You don’t have to make a lick of sense to benefit from them. Narratives are symmetric.

II. Narratives Are Incredibly Prevalent.

We’ve seen that bad results can be hidden in plain sight in the context of psychology by simply slapping a narrative on these. But does this only apply to psychology?

I’m going to demonstrate that it happens everywhere. Sorry, psychology-hating fans, we only focused on psychology first because it’s what I know best.3

So there are a huge number of things you can’t possibly understand. Sometimes this is because you don’t have enough time to do a PhD in them. Sometimes it’s because no one understands them, although we mitigate this by slapping a label onto a field and saying we understand what is happening.

Brief aside on labels, Taleb frequently deploys words from his vocabulary like flâneur, but once nicknamed a guy he hates ‘Fortune Cookie Shermer’. You can’t make this stuff up.

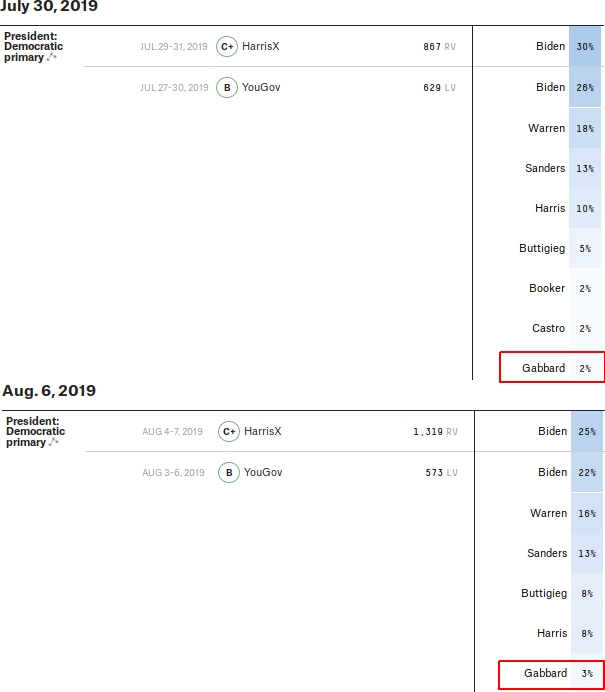

Anyway, there’s the usual stuff about who won the primary debates in the U.S. Ignore the politics right now – I’m picking this example purely because it is recent and clear. After each debate, we get to hear who the ‘winners’ probably are. After the second debate in early August, it was opined that a candidate did really well. I’m not American and have no idea who this is. I don’t care4. But here is what I do care about.

“Tulsi Gabbard: The Hawaii congresswoman entered this debate as one of the least-known candidates in the field. That should change — at least somewhat — after a strong performance. Gabbard was reasonable but also pointed: She did real damage to Harris on criminal justice reform. She was poised and knowledgeable throughout. And she made the most of the relatively limited talking time she had, using it to talk about her resume — most notably her service in the Iraq War. Overall, a very strong performance.”

Cool, cool. I wonder how big the change was –

Wow! Literally five people changed their minds! It’s almost like nothing you just said matters!

People are reading these and thinking they know what’s going on. At the very least, isn’t the journalist heavily implying they know what’s going on, and that the world in this instance makes any sense at all? I didn’t even need to watch the debates. I knew their prediction would have some moronic elements. All I had to do was Google ‘post debate winner’, pick the first article from a major news outlet, then find the first instance where the writer made a testable prediction. It’s like clockwork. With stupid… gears? It was bullshit under a thin veneer of story, is what I’m saying.

III. Extremely Important Interlude

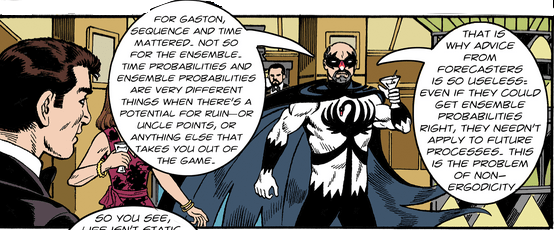

Did I mention there is a webcomic about Taleb? Look at it! It's glorious! But also what the fuck is going on here? What are you saying, old man?

IV.

Yet while this particular brand of nonsense seems ubiquitous in some circles, it was clear that this didn’t happen nearly as much in other fields. Say, a class on machine learning. Why not?

Well, if you make a bad prediction in a machine learning task, you would get an unambiguously poor result, and then you’d be the person that sucks at machine learning. The reason it’s easy to get away with a shoddy narrative other fields is that if you make the story up after the fact, it’ll always fit whatever you just saw. Then to prove you wrong someone would have to get funding, ethics approval, all that jazz. So it’s easy to make up stories, but hard to disprove them.

That seems like a pretty good explanation.

But as I’m writing this, I wonder, have I not just engaged in the very thing I am rallying against? That's sure a neat story. How do people get away with awful political takes and economic forecasts? You can test those. Why isn’t anyone calling them out? Does no one care? Are they getting called out and I just don’t know where to look?

(Note from the future: They are both getting called out and society at large doesn’t care. So uh, fuck us, I guess?)

It’s an interesting question. At least the person from CNN above actually made a testable prediction. I just hope that the lesson they took away was “I actually have no idea how any of this works”, rather than the far more common outcome of coming up with a story to explain why they were wrong.

In contrast to this, FiveThirtyEight famously produces very accurate predictions. And when they look over the actual results following events, they tend to avoid narratives. They fit some trendlines and test some straightforward hypotheses. And here is FiveThirtyEight’s own head honcho Nate Silver apologizing for how all the stories he was spinning made him totally wrong about the previous Republican primary. There’s nothing to be ashamed of there at all because at least he admitted it instead of making excuses. It happens to everyone, but only a few people can just admit they were clueless.

The truth is, people are complicated. The future is opaque. The world is a mess. Or as Taleb loves to quote:

“It's tough to make predictions, especially about the future.”

— Yogi Berra

That is, making accurate predictions is hard if you’re interested in being right, or if you have an outcome you could be punished for. However, coming up with compelling narratives? Super easy. There’s a very famous study about ‘power poses’, again a popular TED talk, it’s always the TED talks. It just so happens that one of the authors has retracted the belief that the effect is real, but the one that gave the TED talk has strongly defended the original work (unconvincingly) and is still raking in the fame. RetractionWatch says that the author is receiving large speaking fees, though following their link I couldn’t find a specific number. Either way, it seems like there’s no real punishment for pushing bad science.

And there’s no shortage of these weird papers:

“How many times have you heard the expression – maybe you’ve used it yourself: I’m going to wash my hands of something. I’m going to move on, I’m going to disassociate myself from something, I’m washing my hands of this. And this idea of symbolically washing yourself clean is something you see in religion too, of course, like the ritual of baptism.

But could there be a little more to the metaphor? Could washing your hands, the act of methodically lathering up with soap and water, have some tangible effect on your thoughts? A study out this week in the journal Science suggests that the answer is yes, that hand washing can actually change your thinking.”

Yes, this study did not replicate. But I’d like to draw your attention to something else entirely. What would have happened if the results came out the other way? My guess is that we would have seen an interpretation like:

“We proposed that the act of washing one’s hands reminds participants of uncleanliness. Washing one’s hands in Western culture is heavily associated with negatively valenced acts, such as ‘washing one’s hands of a crime’.”

If you can come up with a compelling narrative regardless of your results, it seems like the narratives are actively damaging in almost all cases. But there is some inherent tension here, because it seems like establishing a causal relationship between factors requires a narrative. Things fall when they are dropped because of a force called gravity – so we can’t just stop using all sentences that have the word ‘because’ in them if we want to draw conclusions. Also my grandmother refuses to even listen to me talk about normal distributions, so perhaps that test doesn't work on all points either. All we can do is try to figure out is when it’s appropriate to do so.

V. The Inappropriate Use of Narratives is Enforced in Academic Contexts

We have seen that inaccurate results can be hidden in plain sight by appending a short story at the end. But I’ll go even further and say that we are inadvertently training people to think this way, punishing them when they don’t, and even this process is hidden by narratives.

I mentioned earlier that many of the students I know have a rote list of permitted objections to science. This is actually not really their fault – it’s one of the unspoken rules at university. The main reason I was an effective private tutor is that, not being employed by the university, I was allowed to speak the unspoken rules.

I noticed that the university would tell my students (and myself) to do independent research and write up our conclusions but simultaneously tell us what story to tell.

And you had better go with that story – or any story.

So you get an essay about psychoanalysis, with a little blurb saying that ‘evidence shows it is approximately as effective as cognitive behavioral therapy’, plus a couple of articles laying out a simple narrative.

No, no, you don’t have to accept that as true. This is a university, critical thinking is encouraged. But if you don’t, you’ll get marked down and we’ll say your research was weak. What constitutes weak research? Well, you didn’t have enough references (ignoring the fact your peers had far fewer). Oh, you had more references than them? Then you should have elaborated more on fewer articles. Ah, you did both? You've cited too many articles and not included enough of your own thoughts.

How could you have known before submitting this what was too much or too little? Oh, we’re out of time, lodge a complaint if you have any further issues. It will be reviewed by someone that has no incentive to disagree with me.

I wish more of my students had thought to ask that question. How could you have known before submitting the work? For many students, the answer is that you probably couldn’t. There’s a bunch of randomness in marking, and it depends a ton on how your tutor is feeling (and yes, on the quality of your writing). But not on the actual facts of the matter in many courses. There is typically an allowed narrative, and woe unto those who stray too far from it.

Do universities have a sinister agenda to force particular studies down your throat? No, not usually. Does this apply to every unit? No. But it does to most units, most of the time. One of the key pieces of feedback I got on my previous article where I mostly discussed psychology was that every faculty has some version of this problem.

See, you do a bit of digging, and hey, it turns out one of those first references given to you wasn’t quite right. But you know that you have to include the starting references to make sure you’re on topic, plus it’s expected of you. And well, you’ll have to cite it if you’re refuting it.

If you get this far, you have already fallen victim to one of the classic blunders! The mistake here is that you’ve gone and included something that isn’t a narrative. Sometimes studies aren’t false for compelling narrative reasons. The researchers don’t always make a really interesting mistake, or interpret a fact incorrectly. Sometimes you just recruited too many outliers into your sample. It’s bad luck. Shit happens.

If you write “Research thus far has been inconclusive. John & John found a positive effect, but a later study by Bill indicated a negative effect.”, you aren’t getting a high grade. That’s just confusing. Your marker needs closure!

You would be far better off saying “John & John found a positive effect, suggesting that this therapy has become considerably more effective in light of recent cultural shifts.”.

The former demonstrates more research. The latter is a neat story and is easier to read. Don’t complicate things. Just let me read your work and put a big red tick next to it. Do you think your underpaid marker working through their 30th essay actually gives a damn about the total amount of research you did? In fact, do you think they even know why they’re giving you a precise number? Why 81% instead of 80%? Why 80% instead of 79%? At the end of the day, there’s going to be some gut feeling involved, but they’ll come up with some reasons you can’t argue with after the fact.

VI. Another Very Important Interlude

Why does this exist? He even talks like Taleb tweets.

VII.

In all major Australian psychology courses, students are bell-curved to ensure too many people don’t qualify for Honours. Please find the obligatory horror stories here. When a tutor accidentally assigns too many good grades across the class, they are asked in no uncertain terms to pick someone at random and come up with a reason to take marks away (I have insider information on this point). They do it every semester, and the students have no way of telling whether they’ve been given the shaft. The reasons sound great, whether or not they were concocted after the fact.

I once had two students, one of whom got caught plagiarizing about a quarter of their submission, and the other turned in perfectly serviceable work. Same assignment, same semester, same institution. The one that plagiarized scored about 10% higher.

If you’re a student, dear reader, this is the system that you’re putting in charge of your self-worth. Don’t make that mistake. It’s just numbers on paper. Higher numbers are helpful, but they aren’t worth getting depressed or anxious over. I have never even heard of someone being asked for their grades outside of a few niche domains like law.

Can you see how utterly bizarre this is? The university provides students a narrative about the state of the literature. Students are expected to respond with a narrative, or will be marked down because lacking a narrative simply is less enjoyable reading. The markers will come up with a story to justify the assigned grade, which at some level is a function of how happy they were with lunch that day. At no point is the epistemic and emotional damage that this entire process inflicts upon students addressed.

A final, non-psychology example. I have no serious opinions on sociology. I haven’t studied it nearly enough to comment on the field as a whole. However, I did take a unit on sociology that was really tedious, along with some very stupid units in other fields. At the end of it, they asked everyone to write a reflection on what they learned. I think most people have had to sit through this kind of nonsense. But we all know that we have to diligently write down all the trite ways in which the unit radically transformed our views on life.

And that’s really the key. You can get a good grade by saying the unit was amazing in beautiful prose. You can get a lower grade by saying the unit was amazing with less beautiful prose. You can get a bad grade if you complain that the unit wasn’t that good.

If you say that everything in the unit was just post-hoc rationalizations that don’t really explain anything? That’s not even playing the game poorly. That’s flipping the table over, and you’re going to get sent packing with a failing grade. It might sound fun to point out that the emperor has no clothes, but do you know the thing about emperors? They can decide to hang you and no one will stop them. But if you play along?

Of course, your highness, robes of the finest silk. Anyone can see that.5

VIII.

I think I've gotten the gist of what I wanted to say about narratives across, but I wanted to conclude by urging people to give The Black Swan a go. Many people will bounce off it, but there is a lot of deeply useful life philosophy in there.

Lots of people have problems with Taleb, but honestly very few of them bother me at all. He was the first person that got me seriously interested in statistics, and insofar as I have ever been effective, it has been because The Black Swan managed to convey its message in a way that made it feel relevant to my life. I view everything through the lens he gave me – and it has some downsides, which maybe I’ll cover some other time, but it has no doubt been a huge positive impact on my life.

With that, I believe I’ve said what I wanted to say about Taleb. He is possibly a terrible person, or a great person, or a genius, or an idiot. He wouldn't care what I think because I like his biggest idea and he’s rich. But I feel like I should leave on a more appropriate note.

Hm. Perhaps an anecdote about – No. Ah. Of course.

Perfection.

-

Many readers will have to decide whether an insult from Sam Harris is a good or a bad thing. ↩

-

You shouldn't be happy with the summary of a book because we don't have the minds of fucking eight year olds, but I must be expedient instead of reprinting the whole thing. By the way, did you know there is what appears to be a thriving business in book summaries for leaders? Explains a lot! ↩

-

I've now worked in a bunch more places and can confirm that tech is also bullshit-driven! By the way, I need a static webpage with an enquiry form, can someone recommend a React developer? ↩

-

Mein Gott, do you all remember not caring what's happening in America? Fuck, how I long for those sweet summer days. ↩

-

In other news, local civilization creates globe-spanning, career-limiting industry in screening the population for submitting to arbitrary authority, is shocked when population submits to cryptofascist authority. ↩